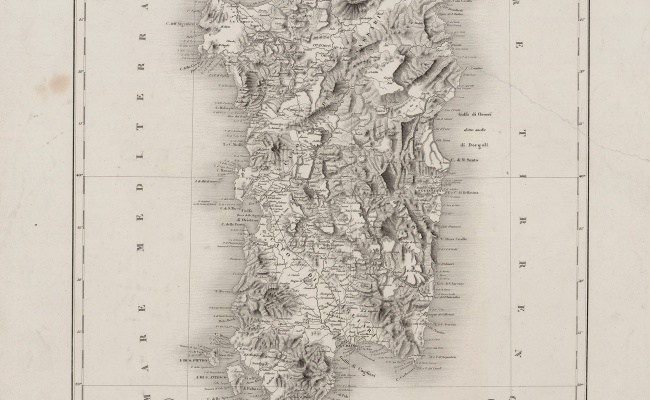

The construction of Strada Reale Carlo Felice, a main road running through Sardinia, in the 1820s made it easier to travel between the northern and southern parts of the island. And the village of Macomer became Barbagia’s ‘port’, an outpost for setting out to discover the Nuoro region.

Travel in Sardinia between the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Description

One of the first travel books about Sardinia was Alberto della Marmora’s Voyage en Sardaigne, de 1819 à 1825, which was published in 1926 (and followed by the same author’s three-volume Itinerario nell’isola di Sardegna in 1960). In this volume, Barbagia is described in tones that reveal sincere interest in the island’s customs, traditions, archaeology and history, but also a feeling of unease about a region perceived as mysterious and wild.

This dual point of view, at once both fascinated and fearful, is typical of the accounts of travellers who ventured into the middle of the island. From Gaston Vuillier and Charles Edwardes to Valery (Antoine-Claude Pasquin) and D.H. Lawrence, who observed in his travel diary Sea and Sardinia (1921) that ‘Sardinia is another thing’, numerous foreigners travelled to the island in search of fortune or simply new experiences.

Sardinia was also a destination for ethnographers and anthropologists, like Paolo Mantegazza, Lamberto Loria – who travelled the island with the furniture maker Gavino Clemente to gather objects for a major ethnographic exhibition (Mostra Etnografica) in Rome in 1911 – and Julius Konietzko, who visited Sardinia in 1931 for the same reason, on behalf of the Museum für Völkerkunde, Hamburg. And also artists: the Spanish Costumbrista painters Eduardo Chicharro y Agüera, in 1901, and Antonio Ortiz Echagüe, between 1906 and 1908, found the perfect settings for their folkloric subjects in the villages in the island’s interior, especially Atzara (some of their paintings are on view at MAMA).

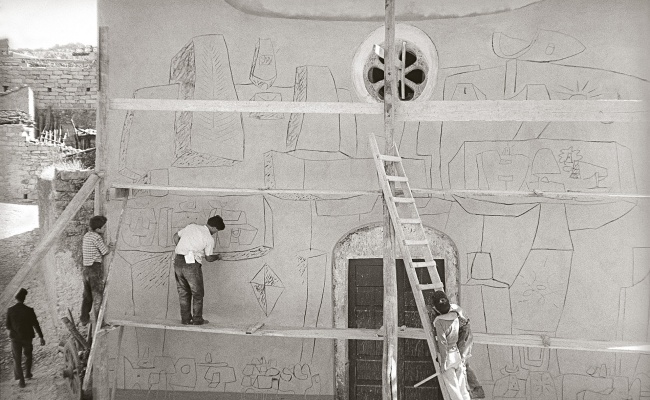

In the 1950s, Sardinia, and its hinterland in particular, was the subject of at times contradictory accounts, like the photojournalism of Carlo Bavagnoli. In 1958, the photographer covered the arrival of modernism in Orani, with the decoration of the church of Sa Itria and the exhibition in the streets of the town of sculptures by Costantino Nivola, but the next year, in 1959, he published ‘Sardegna: l’Africa in casa’ (Sardinia: Africa at Home) in l’Espresso, focusing on the island’s extreme poverty and backwardness.

Barbagia was discussed as part of the ‘southern question’ in Carlo Levi’s Tutto il miele è finito (All the Honey is Gone), an account published in 1964 of two trips, in 1952 and 1962, during which Nuoro, Orgosolo and Orune were the towns that most stood out for the author of Christ Stopped at Eboli.

There were those who arrived and left again but never forgot, like Elio Vittorini in 1932, who won a prize from the weekly L’Italia Letteraria and wrote reams about the island, including Sardegna come un’infanzia, published by Mondadori in 1952, and those who stayed, like Marianne Sin-Pfältzer, who documented the changing society and landscape in thousands of photographs between 1955 and 2015, making the Nuoro region into a special observation post for witnessing and recording that change.

Nuorese Cultural District

Nuorese Cultural District